[Two butterflies in a meadow*]

The singly most discussed issue with and between translators is how much

to charge for a translation. I suppose

that is true for many other service providers. The obvious but irrelevant

answer is as much or as little as possible, depending on whether the party is

the provider or purchaser. The main problem is the exact manner of establishing

that rate. Also, this approach often leads to short term business relations if

the price is unrealistic in the long term. On a more scientific basis, many theories

exist but don’t actually apply to the setting of translation services. Therefore,

I will suggest a simple but potentially emotionally unsatisfying way of

establishing the value of translation.

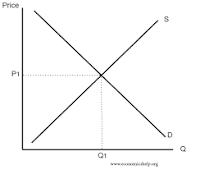

[Supply and demand graph]

Learned economists would tell us that market price is determined by

identifying the intersection point between the supply and demand lines on a

graph, a visually pleasing solution. To

be fair, these same economists also mention in the small print that these

graphs are relevant only when all parties have full knowledge of this supply

and demand as well as the current state of sales. For example, if I want to buy

a certain power drill, I can check the prices at all local stores selling that

product and choose the least expensive option. If a store fails to move its

inventory, its price is too high. Please note that all the prices are posted,

the product is identical in all stores and the number of power saws available

can be determined by checking inventory. None of these factors is true in

translation. Translators have no idea nor does in many cases the law allow them

to discover prices. No translation is identical in style or quality. As an

Internet service, the number of competing translators is indeterminate. Even if

it was possible to identify the magic rate, it would change in a short time,

which is what actual rates do not even do when there are universally available

changes in currency exchanges rate. Therefore, the graph is charming but

useless.

[Cost + Profit = Selling Price]

A simpler manner of establishing prices is the “cost plus” method. In

this, the supplier determines the total cost of providing the good or service

and adds a profit factor. Back to our power drill, taking into account the cost

of purchasing the drills and additional costs, which include rent, insurance,

theft and payroll, the merchant establishes the minimum worthwhile price to

sell the product, at least in theory. Again, this idea sound reasonable but is not

usually practical. Even in regards to physical products, most merchants cannot

really ascertain how much the additional factors should impact the price. As

for services, no product needs to be purchased to provide a specific service

nor is the quantity and volume predictable in the least. The best a service

provider can do is to calculate minimum income to pay to keep a roof over their

head and food in the fridge. Even with this information, it is impossible to

establish the price for a translation or other service.

[Crocheted orchid]

(C) All rights reserved Tzviya Levin Rifkind

Just for intellectual exercise and purity, it is worth considering Marx

and Engel’s approach. They stated that the value of a product and, by extension,

a service, is the measure of the value inputted by the worker. As an example, a

given translator with 20 years’ experience and specializing in financial

translation provides a brilliant German version of a French annual report. The

value of the worker’s contribution in terms of knowledge and effort is immense

and should be fully rewarded, at least according to those fine gentlemen. The purchasing company probably won’t be

willing to pay that amount regardless of the translator’s background or effort.

To illustrate, my wife crocheted an orchid for her daughter’s wedding. It took

hundreds of hours of work and all her skill. If she were to sell it, according

to Marxist theory, she should get a princely amount. Alas, regardless of how

beautiful and special it is, the chances of her getting that price are very

close to zero. Unfortunately, skill and effort are important but not

determining.

[Bell curve]

For those without extraordinary skill or knowledge, the bell curve seems

to provide a relevant guide. These service providers should set the price based

on the most common rate in the subject and physical area, rendering them

competitive with most potential customers. Unfortunately, translation is not a

physical good and is, consequently, not limited to a given physical area.

Through the Internet, translators from all over the world as well as low-cost international

agencies can and do compete for the same customers. The playing ground is not

even as the cost of living can significantly differ from place to place,

allowing some to lower their rates to below the living costs of others. Not

only that, the customer may not be to ascertain nor care about the quality of

the translation. The service purchsers themselves are based in a wide variety

of countries, each with its own economic reality. The business environment in Egypt

and Germany is extremely different. Therefore, rendering the Bell Curve

irrelevant.

[Two hands - two worlds]

An analysis that is much easier to implement and subjective

than those mentioned above is that the best price is that in which both the service provider

and customer are satisfied. If the translator or other service provider earns enough money to feel

properly rewarded, however much that is, while the customer receives value,

however it defines it, both parties gain in terms of stability, energy

efficiency and results. The calculation

of the relevant factors will naturally vary. The price is established by direct

negotiation with each side considering its situation. There is no requirement

for expensive and time-consuming market research nor is any amount set in stone

as the rate can be renegotiated as circumstances require. For example, if the

transaltor is not paying bills or the purchaser needs to cut costs, the rates

eventually change. In practice, this is

how most rates are set.

This approach requires a sometimes difficult emotional acceptance that others may be attaining

higher or lower rates, even significantly so. In a sense, it is “autistic” in

that it filters external reality. On the other hand, this mutual agreement

creates its own reality in that it is possible to reach a mutually acceptable situation

with some partners but not with others. It is clear that those in the “the

more, the better” school will not adopt this approach. To drag Voltaire into the

discussion, I tend to stand with Candide, who said that il faut cultiver son jardin.

* Always include a caption below pictures to allow blind readers to also enjoy.

* Always include a caption below pictures to allow blind readers to also enjoy.